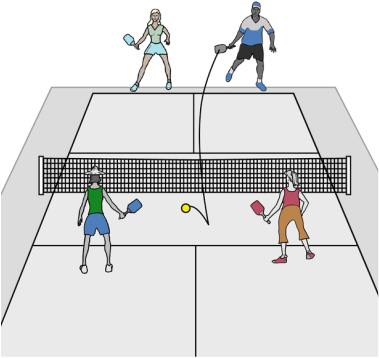

Mastering ball placement is critical for attaining higher levels in pickleball play. What factors determine where your ball will land?

1) The angle of your paddle (up and down & left and right)

2) The angle of your swing (up and down & left and right)

3) Your wrist movement, if any

4) The power behind your hit

5) Spin

Before you concentrate on ball placement, though, you must first consider how you contact the ball. Focus your attention and skills (such as good footwork and proper form with your stroke) to the contact of the ball. Only after this focus on ball contact should you consider how you place it on the court.

Take time to get into position early enough to take a proper backswing before hitting the ball. If that means halting in mid-court, so be it. Stop, prepare your swing, and focus on contacting the ball. Many players say you should think about “swinging through the ball,” as this makes

RSS Feed

RSS Feed